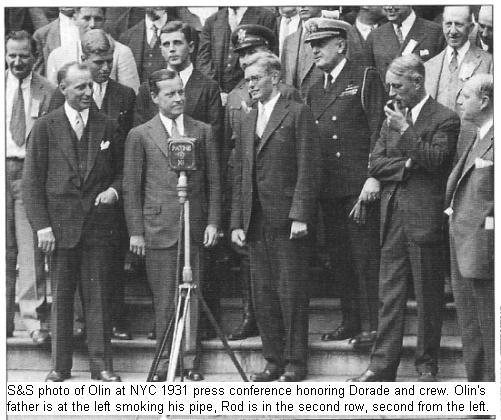

Dorade was the boat that brought Olin Stephens to the attention of the nautical world. The young designer skippered his design to a spectacular victory in the 1931 Transatlantic Race with his father and brother in the crew. It earned them a ticker tape celebration in New York City on their return. Many articles have been written about Dorade and Olin’s feat. Dorade’s recent restoration has also been in the news. Bruce Knecht’s article that appeared in Scuttlebutt in 2007 tells the Dorade story very nicely, and is copied below. She is back sailing in Northeast waters. Watch for her.

Updated September 9, 2013

Original article posted on Dolphin24.org found here.

——

Scuttlebutt News:

Olin Stephens’s Radical Yacht

By G. Bruce Knecht – Photos by Cory Silken

Dorade is 75; its maker is 98–and they both remain (sea)worthy of admiration.

(November 6, 2006) OLIN STEPHENS’ obsession with sailboats took hold shortly after World War I during a childhood visit to Cape Cod. He didn’t just admire them. He studied them with what he later described as “great concentration,” sketching any he thought might be worth emulating and imagining how he might do things differently. By the time he was 20, Mr. Stephens had dropped out of M.I.T., had brief apprenticeships with several leading yacht designers, drawn up plans for a handful of small boats, and formed his own company, Sparkman & Stephens. On the basis of Olin’s early promise, his father, who had recently sold the family coal-supply business, placed an order for a relatively large yacht, a 52-foot yawl. When Dorade, named for the dolphin that is correctly spelled Dorado, was launched in 1931, it sparked a revolution.

It was strikingly slender, its beam just 10-foot-3. It was also, by the standards of the day, extremely lightweight, in part because the frames that supported the hull were made from steam-bent sections of wood weighing far less than conventional and much bulkier sawn frames. Until then, it was believed that ocean-going stability could not be achieved without a much broader and heavier hull. Dorade’s stability came from a different source-a lengthy lead keel that put the ballast far below the waterline, where it would be much more effective in counterbalancing the force of the wind.

Thanks to the combination of a streamlined hull and “outside ballast,” Mr. Stephens was certain Dorade would be fast. It was also strikingly beautiful. Like most designers of that time, he believed boats that were pleasing to the eye were also faster than unattractive ones. Dorade’s bow and stern rose from the water with curvaceous grace, creating the elegant overhangs that are hallmarks of classic sailing yachts.

But Dorade represented a major risk. Mr. Stephens had created a radical new design without the computer analysis and tank testing that is now commonplace. He had relied upon instincts alone, intuitive judgments of how a vessel’s lines would affect its performance. The lack of precision was obvious the moment Dorade was launched: The white stripe that had been painted around the hull to mark the waterline disappeared as it sank three inches below the surface. When Mr. Stephens announced that he was going to enter Dorade in a trans-Atlantic race, many yachtsmen thought he was foolhardy.

Mr. Stephens was the skipper and navigator during the race, which set out for England from Newport, R.I., on July 4, 1931. His seven-man crew, which included his younger brother Rod, who had overseen the yacht’s construction and would become a partner in Sparkman & Stephens, was young: Even with the inclusion of the Mr. Stephens’s 46-year-old father, the average age was just 22.

Olin Stephens was at the helm when Dorade crossed the finish line on July 31. Longer sailboats generally go faster than shorter ones, but Dorade, the third smallest of the 10-yacht fleet, reached the line more than two days before the second-place boat. When the times were handicapped, or “corrected,” to reflect the differences among the yachts, Dorade’s time was almost four days better than its closest rival. Dorade went on to win the Fastnet Race by a wide margin. When the crew returned to New York City, where Sparkman & Stephens had its office, they were rewarded with a ticker-tape parade, a first for sailors.

And yacht design would never be the same. The assumptions that had limited naval architects to incremental advances were abandoned and the modern age of racing design, defined by an endless quest to produce lighter but more powerful yachts, commenced. No one benefited from this more than Mr. Stephens, who became the most successful designer of the 20th century, creating plans for six successful America’s Cup defenders, two of which were two-time winners.

Dorade also became a legend. The Stephens family sold it in 1936, but successor owners have underwritten the ceaseless work of maintaining an aging wooden vessel. In recent years, it was based in the Mediterranean, where an Italian owner competed in Europe’s active classic yacht racing circuit. But since it was acquired by Edgar Cato, an accomplished American yachtsman, about a year ago, it has been based in Newport. “It was a piece of history that I had read about for most of my life-and I decided that I wanted to bring it back to the United States,” Mr. Cato explained.

Over Labor Day weekend, he and Mr. Stephens, now 98 but still traveling to yachting events around the world from his home in Hanover, N.H., boarded Dorade to compete in the Museum of Yachting’s annual Classic Yacht Regatta in Narragansett Bay. Although Mr. Stephens himself advised the crew on the most favorable sail combinations, Dorade placed second after a section of the rigging failed in winds gusting to more than 30 knots. “We would have won otherwise,” said Mr. Cato, who plans to continue racing Dorade in the Caribbean and New England.

Over Labor Day weekend, he and Mr. Stephens, now 98 but still traveling to yachting events around the world from his home in Hanover, N.H., boarded Dorade to compete in the Museum of Yachting’s annual Classic Yacht Regatta in Narragansett Bay. Although Mr. Stephens himself advised the crew on the most favorable sail combinations, Dorade placed second after a section of the rigging failed in winds gusting to more than 30 knots. “We would have won otherwise,” said Mr. Cato, who plans to continue racing Dorade in the Caribbean and New England.

Unfailingly modest, Mr. Stephens is reluctant to rate Dorade as a masterpiece. When I spoke to him a couple of weeks ago, he said it was too narrow, that it would go even faster, and be less “rolly,” if he had given it just a bit more breadth. But he acknowledged that Dorade was a breakthrough-or, as he put it, “a kind of awakening”-for yachting design. “I knew that a lighter boat with outside ballast was the way to go, and that a deep and narrow hull would go through the sea nicely. It was obvious. It was like taking candy from a baby. It just had to win.”

Mr. Knecht is a Journal reporter and the author of “Hooked: Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish.”

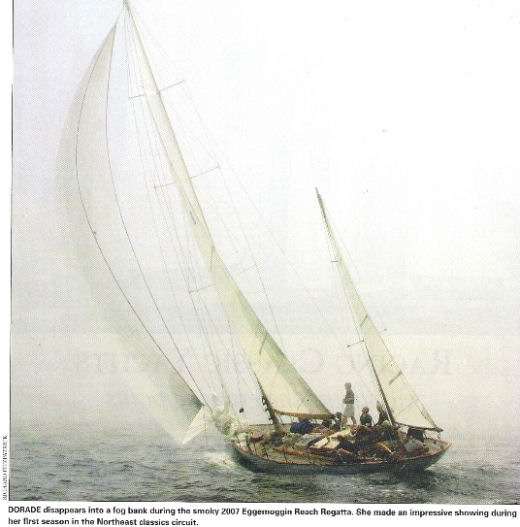

Dorade was featured in Newport’s 2008 Museum of Yachting’s tribute to Olin Stephens’ 100th birthday, and Wooden Boat Magazine’s March/April 2008 issue had an excellent article by Joshua Moore about Dorade and her restoration. The following is a photo by Richard Fitzpatrick from Joshua Moore’s article – Dorade racing in the 2007 Eggemoggin Reach Regatta.

Dorade won the 2009 Sparkman &Stephens Association World Global Challenge Trophy, narrowly beating out a Dolphin 24, Marionette. This award is presented annually to the best racing performance by an S&S designed yacht.

Dorade won the 2009 Sparkman &Stephens Association World Global Challenge Trophy, narrowly beating out a Dolphin 24, Marionette. This award is presented annually to the best racing performance by an S&S designed yacht.

September 9, 2013. Better late than never we recognize Dorade win at the 2013 Transpac race. We were prompted by the receipt of a photo of Dorade on San Francisco Bay during the America’s Cup Finals late last week.

Here is the text of the Mystic Seaport Museum report covering Dorade’s win at the 2013 Transpac Race

DORADE WINS TRANSPAC

HONOLULU, HAWAII – In a feat few would have predicted, the 1930 Sparkman & Stephens-designed 52-foot wooden yawl Dorade has earned overall victory in this 47th edition of the Transpac race, organized by the Transpacific Yacht Club and held biennially since 1906. Dorade was awarded the impressive King Kalakaua Trophy as First Corrected Overall Yacht.

According to a Transpac press release, Dorade started the 2225-mile race on Monday, July 8, at 1 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time and crossed the finished at Honolulu’s Diamond Head on Friday, July 20, at 3:23:18 Hawaii time, for an elapsed time of 12 days 5 hours 23 min 18 sec. Over the course, she turned in an average speed of 7.8 knots, 8.1 percent faster than her performance in 1936. She also hit a lifetime record speed of 15.9 knots.

This is the second time Dorade has won: the first was in 1936. In the 1930s Dorade amassed a racing record unmatched for her time, with victories in the Newport-Bermuda, Fastnet, and Transatlantic races, and it is unprecedented for a classic yacht of this era to also score so well in a mixed fleet of modern yachts.

“We thought if we could match Dorade‘s 1936 record of thirteen days that would be absolutely fantastic,” said owner Matt Brooks in the release. “We actually beat that record by more than a day. To do what we’ve done exceeded all our expectations.”

Brooks and his wife Pam Rorke Levy bought Dorade in 2010 and spent more than a year refitting it for ocean racing, with the goal of repeating the many races the boat won in the 1930s, a record of wins that stands unbeaten today. They entered the 83-year-old Dorade in the Transpac against the advice of many in the sailing community, who view the boat as an irreplaceable piece of maritime history. Sea trials and constant refinement of the boat’s systems have been ongoing over the past three years.

“Really there were eight of us on this — seven crew members and the eighth was Dorade — and she didn’t disappoint us,” said Brooks. “She performed flawlessly and did everything we asked her to do.”

Brooks sailed with Navigator Matt Wachowicz, Tactician Kevin Miller, Watch Captain Ben Galloway, Eric Chowanski on the Bow, Hannah Jenner on the helm, and John Hayes as sail trimmer.

Posted in Maritime History on July 29, 2013.